The Challenge: We assume we should play to our strengths to be successful.

The Science: When we fail at something, we think we should do something else instead.

The Solution: Here’s why!

You’ve failed at something again: that date you loved didn’t lead to any follow-up calls, the project you worked so hard on was picked apart by your boss, or your New Year’s resolution lasted about 1 and a half days. When faced with a challenge or failure, you often assume that you just don’t have what it takes. “I scare away romantic partners.” “I suck at my job.” “I have zero willpower.” In the face of failure, you assume you’re a failure, give up, and feel terrible. Why is that and what can we do about it?

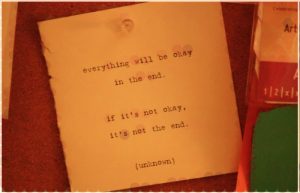

Consider this approach to failure:

- Had R. H. Macy assumed he was not made for business after the first five stores he created completely failed, he would never have founded the wildly successful Macy’s stores.

- Had Bill Gates assumed that computer start-ups were not for him after his first company, Traf-O-Data, went under, he would never have founded Microsoft.

- Had Dr. Seuss (whose real name was Theodor Seuss Geisel), the celebrated children’s writer, concluded that he was not a good author after his first manuscript was rejected not just once but over twenty times, he would never have revolutionized children’s literature.

- Had Albert Einstein, after having a speech impediment as a child, being expelled from school, and being refused admittance to university assumed he was not smart, he would never have gone on to be the world-renowned scientist and Nobel laureate. Einstein simply did not buy into the strengths idea: “Failure is success in progress,” he is quoted as saying.

We generally assume that what distinguishes extraordinary people, such as star singers, bestselling authors, famous movie actors, or self-made billionaires from the rest of us is their particular strengths. We think these people have a special gift. They may have a knack for business or an artistic bent or some other “it factor.” We believe their inherent strengths set them apart and therefore make them successful. Conversely, if the rest of us don’t reach their heights, it is because we lack such gifts. You’ve either got “it”—whatever “it” may be—or you don’t, and there’s not much that you can do about it.

We think about our own strengths in similar ways. You might think of yourself as a math person or not, a people person or not, a creative person or not. Ultimately, you believe, your success is predestined by the natural abilities and gifts you are fortunate to have. You simply play the hand you’re dealt.

This belief that we are born with certain innate strengths that determine what we can and cannot achieve severely backfires on us—especially in times of failure or challenge. Over decades of research across a wide array of failure scenarios, Carol Dweck, Stanford University developmental psychologist, has shown that believing that we either have certain strengths or not is damaging both personally and professionally.

Believing in strengths leads to the following kind of logic: “If I fail to successfully put together a financial model, it reveals that finance is not a strength of mine. I should probably not work in finance.” Having pigeonholed yourself as “not good” at the particular task you failed at, you feel hopeless about your abilities in that area, preventing you from learning from your mistake and developing new skills. If you stop persevering in anything outside the areas you are good at, you simply cannot expand your sphere of knowledge or competence.

Believing in strengths can be particularly damaging professionally if, for example, you work in a field that is always changing and evolving— which many of us are doing. For example, if your industry is expanding to China or Japan, you may want to learn these languages. However, if you believe that languages are not one of your strengths, you won’t even try. Your belief, of course, becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. Chances are that your knowledge and skill set will forever remain limited to the areas of your life that you see as strengths.

Perhaps more importantly, when you believe in strengths alone and you aren’t successful—not getting into your first choice university, not getting that job you wanted, not getting the promotion you thought you deserved, not being in a good relationship—you are devastated. You become hopeless because you assume you can’t progress in those areas. Unsurprisingly, research shows that subscribing to the idea of strengths is linked to higher levels of depression, probably in part because it leads to excessive self-criticism.

So next time you find yourself thinking that you’re “just not good at” such-and-such a thing, throw that thought out the window. Remember that neuroscientific data clearly demonstrates that our brains continue to grow new neuronal pathways throughout life. The brain is designed for development and to learn new things. While particular skills may come more easily, we are wired to engage, thrive, and grow in any number of areas, from playing the violin to learning to drive a stick shift, from mastering Chinese calligraphy to excelling on the Certified Public Accountant exam.

Of course, this is not to say you should not engage in work that comes easily to you or suits your natural inclinations. But research has persuasively shown that you shouldn’t let yourself believe that you are limited to being good at the activities that come easily for you. You may have enormous potential waiting to be uncovered.

Adapted from THE HAPPINESS TRACK by Emma Seppälä, Ph.D. Copyright © 2016 by Emma Seppälä, Ph.D. Used with permission of HarperOne, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

To read more about the science of happiness and success, see Emma Seppälä’s new book: